WAR GRAVE

CHARLES HENRY BUTT (grave 75)

FLIGHT LIEUTENANT

1518 BATF

ABOUT MY LIFE

Born: 4th August 1920

Died: 4th November 1942

I was born in Thames, New Zealand, the Son of Ernest Alexander and Hilda Jessie Butt, of Hamilton, Auckland. In civilian life I was a clerk. My younger brother Pete had this to say about me:

“Charles Henry, known to all as Jim was my immediate senior in the family. Because of the depression Jim had to leave school after the fourth form and had two unsatisfactory jobs, car painting and furniture polishing, before joining the borough council as a clerk (which he hated according to the family). Grandfather came from a well-established Gloucester family where he left at an early age and ran off to sea. Whether he committed a misdemeanour or not is not quite clear.

He married in Australia before settling in Whangarei, New Zealand.

Jim’s father was the oldest of 10 children. He was self-taught and became a reporter for New Zealand’s largest newspaper and later ran the Waikato branch based in Hamilton where they lived. Jim was born in Thames, a small coastal town started during the gold rush. Jim attended Hamilton Technical College where he was in the 1st eleven and 1st fifteen. The family didn’t own a car during the depression, but father used to own a motor bike which he drove very sedately. On one occasion he returned without Jim who had been riding pillion. To mother’s question “Where’s Jim’ he had no answer. Jim had been jolted off somewhere along the road, but was no worse for wear.

I was 17 when war broke out, and my brother Jim decided to join the Air Force, tackling the assignments prior to being accepted. He was less a student than I, but of course had less schooling. He enlisted in the Third War Course of the RNZAF in 1940 and after attending the initial training wing at Levin, and the Elementary Flying Training School at New Plymouth, was posted to Woodbourne Blenheim where he flew Vincent Wildebeests.

Receiving his flying brevet or “wings” he left New Zealand in 1941 and was posted to an operational training unit at Lossiemouth, Scotland, where he converted to Wellingtons. Attached to 57 squadron at Feltwell, Cambridge, he completed 10 bombing operations as a second pilot, before commanding the aircraft for a raid on Munster. This trip was aborted because an engine overheated, but there were many more.

On his 31st trip over enemy territory the aircraft was chased by an enemy night fighter, but managed to escape. His first tour over, Jim was posted as an instructor to No. 18 Blind Approach Flight at Scampton, five miles from the City of Lincoln. He was commissioned and eventually became a flight commander with the rank of Flight Lieutenant.

A highly competent navigator in foggy conditions, his competence was recognised by a recommendation for an Air force Cross. Assessed as an above average pilot in Blind Approach Systems, he was expecting to return to operations. Before being posted to a squadron and receiving the recommended award, equipment failed as he was about to touch down and his aircraft hit a tree on the edge of the runway.

His death was a tragic shock to my parents. It wasn’t until she and my father visited the grave twenty years later that my mother finally accepted Jim’s death. I attended his funeral at Scampton in 1942, and was privileged to make a pilgrimage to his grave in 1986. We were good friends, and his death affected us all.

Returning from a scramble at Bolt Head on November the 4th 1942, I was told by the Flight Commander, Dusty Miller (he was later killed ) that my brother Jim had died in a flying accident at Scampton. I was shocked – Jim was a very experienced pilot.

Our first meeting after my arrival in England was on a bus on my way out to Scampton to see him. I hadn’t then known he had been commissioned, and I didn’t recognise him immediately in his Pilot Officers uniform. We met on another occasion at Nottingham, where we stayed in the same hotel. I remember that night, because I escorted a girl home from a dance without realising that we were travelling on the last bus. I had a long walk home.

Given leave to attend the funeral, I flew my Typhoon back to squadron headquarters at Exeter, and was allowed to take the Tiger Moth to Lincoln. With visibility down to a few hundred yards, I flew in murky conditions over the Midlands. I didn’t realise I was over Coventry until I saw a large anti-aircraft balloon at the same level and not far from the line I was flying. After refuelling, I saw the tower of Lincoln Cathedral standing out of the fog, and was soon landing at Scampton.

As Jim was by then a Flight Lieutenant, there was a significant attendance of brass hats, bands and airmen at the funeral. I don’t remember meeting the padre but assume I did. Jim’s colleagues were very supportive. It was a lovely Sunday morning when I took off from Scampton and headed south. The petrol gauge in a Tiger Moth isn’t easy to read from the back cockpit, but when I thought fuel was becoming low I landed on an aerodrome which turned out to be a maintenance unit. There was no one about on Sunday. I took off again in the knowledge that there were many aerodromes further south. I had just begun to traverse the Salisbury plains when the propeller stopped turning. I had run out of petrol.

It was all very embarrassing, but fortunately, there under the left wing was a grass covered aerodrome a little distance away. I stretched the glide as far as I could and only just made it. In fact I landed just inside the boundary fence and pulled up before reaching the track which formed the circumference of the main field. Given the informality of my preparations for the flight I couldn’t have picked a worse place to land. It was Upavon, the headquarters of the training command. First on the scene was the Station Warrant Officer, who took me to the Chief Flying Instructor and the Chief Ground instructor. With no flight plan, I had in their eyes broken every rule in the book. Before I was allowed to proceed I had to produce a plan which passed their careful scrutiny. I was made very humble. However once away I had a good look at Stonehenge, and followed the railway line back to Exeter”.

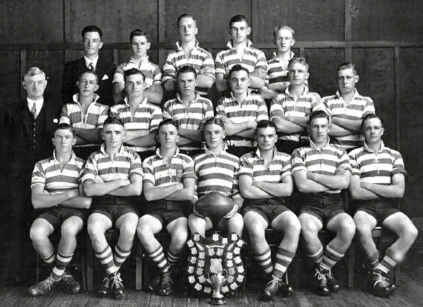

The Hamilton Technical Old Boys’ Colts 1939. In the Championship they played 15, won 15 with 221 points for and 66 points against. Charles Butt is front row second in from the right as viewed.

MY AIRCRAFT

The Airspeed Oxford was a very widely used twin-engine training aircraft during World War 2. It first flew on 19th June 1937 and remained in RAF service until 1956, with 8751 being built over that period.

MY ROLE

I was one of two pilots on board this aircraft. I was the instructor pilot teaching the student how to use the Beam Approach system to make landings when the weather was so poor that you can’t see the runway.

MY SQUADRON

1518 Beam Approach Training Flight had formed at Scampton less than 5 months earlier, to train pilots in a new electronic aid which would allow them to safely land their aircraft when they could not see the runway.

The system transmitted a narrow beam out from the centreline of the runway, a receiver set on board the aircraft, codenamed Rebecca, translated this signal into an audible Morse tone, which the pilot could use to line himself up on the runway.

If the pilot was one side of the runway he would hear dots and if he was on the other he would use dashes. The intensity of these signals would tell him how far he was from the centreline.

A Pilot standing in front of an Oxford belong to the Beam Approach Training Flight complete with the units bat motif (BATF).

THE ACCIDENT

The weather at Scampton was very poor and as one of the flight’s most experienced pilots, I was asked to conduct a weather flight. The idea of this flight was to get airborne and find out just how bad the weather was and whether there was any possibility of conducting other training flights; after all, the whole point of the Beam Approach Training Flight was to teach pilots to land in very bad weather.

Together with my student Robert Shaw, we got airborne in Oxford AT663, but it soon became apparent that the Beam Approach set was not working properly and we contacted the control tower to inform them of our problem. With a landing at Scampton now impossible, they advised us to fly further south, where the weather was much better, and land at either North Luffenham or Bircham Newton which were both fit for visual landings.

Our aircraft was heard flying overhead Scampton and the control tower fired two maroons, possibly to assist us in locating the airfield. Shortly afterwards, our aircraft was heard to make an approach, but we were well off the runway centreline. At 14:30hrs we crashed close to Grange Farm in Brattleby, there were no survivors.

Our commanding officer had this to say in the subsequent investigation of our crash:

“This pilot was a very experienced Beam pilot in whom I had complete faith. It is beyond my comprehension why he came down so low as to hit the trees knowing the visibility was bad. Had he flown south he could have landed normally in good visibility.”

The full circumstances of this accident were never fully investigated and the authorities were quick to blame the pilot. However, it is entirely possible that the beam approach set began to work again, only to fail at the last vital moment, we shall never know.

CASUALTIES – 4TH NOVEMBER 1942

Fg Off Robert Shaw (Student Pilot) (Buried Scampton) MORE

Flt Lt Charles Butt (Instructor Pilot) (Buried Scampton)

ON THIS DAY IN WORLD WAR TWO – 4TH NOVEMBER 1942

Guadalcanal, after wiping out a pocket of Japanese resistance, US forces dig defences near Cruz Point.

In North Africe, the German General von Thoma is captured.

Churchill chairs the first meeting of the anti U-boat committee.