WAR GRAVE

JAMES A. G. BROWNE (grave 55)

SERGEANT

49 SQUADRON

ABOUT MY LIFE

Born: 31st December 1917

Died: 31st January 1943

I was from Roma in Queensland, Australia and joined the Royal Australian Air Force on 4th June 1940.

I was married to Majorie Sylvia Browne and we lived at 11a Arnos Grove in London, we had married little more than a month before the accident. In civilian life I was a Grazier, which is an Australian term for a person who raises cattle or sheep for market. I had worked in this business with my father and uncle, since leaving school at the end of 1934.

Prior to joining the Air Force, I undertook some pilot training at my local flying club, in a Gipsy Moth aircraft, achieving 21 hours flying time, which include 4 and a half hours solo flying.

I was 5ft 11 ins tall, had brown hair and blue eyes and I had represented my school in cricket, football and rifle shooting.

MY AIRCRAFT

The Avro Lancaster was a development of the ill-fated Avro Manchester. The twin engine Manchester had been an unmitigated disaster, under-powered and crash prone. Undeterred, the designer Roy Chadwick increased the wingspan and added two more engines. From a disastrous start, the most legendary bomber of all time was born.

From 1942 onwards the Lancaster, together with the Handley Page Halifax, provided the backbone of bomber command. Equipped with four Rolls Royce Merlin engines, the same engine which powered the equally legendary Spitfire, the Lancaster could deliver 18,000 lbs of bombs to targets up to 2500miles away. Later versions of the Lancaster carried even bigger specialist bombs designed by Barnes Wallis of Dambusters fame.

During the Second World War, The Lancaster conducted a total of 156,000 sorties and dropped 608,612 tons (618,378,000 kg) of bombs. A total of 7377 Lancasters were built, of which 3736 were lost to enemy action and accidents.

Today, only 17 complete Lancasters survive, with just two flying examples. The Battle of Britain Memorial Flight’s PA474 and the Canadian Warplane Heritage’s FM213.

Crew: 7

Span: 102 ft

Length: 69 ft 6 in (tail up)

Height: 20 ft 6 in (tail up)

Empty weight: 37,000 lbs

Loaded weight: 65,000 lbs

Engine: 4 x Rolls-Royce Merlin 24 V-12 engines

Engine power: 1,620 hp at 3,000 rpm (1,208 kW)

Maximum speed: 275 mph

Range: 2,530 miles with 7,000 lbs of bombs

Ceiling: 22,000 ft

8 x .303-caliber machine guns

18,000 lbs of bombs

Avro Lancaster bombers nearing completion at the Avro and Co Ltd factory.

MY ROLE

I was the Wireless operator and Air Gunner on this aircraft. When not using our radio to send and receive vital information, I manned one of our aircraft’s three machine gun turrets.

A Lancaster Wireless Operator.

MY SQUADRON

Motto: Cave Canem

Beware of the Dog

49 Squadron was formed at Dover on 15 April 1916 under the command of Major A S Barratt MC and spent its first 18 months as an aircrew training unit equipped with BE2Cs and RE7s. Other documents record that the squadron also trained using Martinsydes. In November 1917 the squadron was re equipped with DH4s and moved to La Bellevue aerodrome in France. Here the squadron was employed in the day bomber role as part of the 3rd (Army) Wing. Its first raid was made on 26 November 1917. Following the end of hostilities, the squadron was disbanded on 18 July 1919. According to its records 49 Squadron destroyed 56 enemy aircraft drove down another 63 out of control, dropped a total of 120 tons of bombs and operated from 10 airfields in France during the 1914-18 War.

On 10 February 1936, 49 Squadron re-formed at Bircham Newton from a nucleus provided by ‘C’ Flight of No 18 Squadron. It was equipped with Hawker Hind light bombers and initially commanded by Flt Lt J C Cunningham. It moved to Worthy Down in August 1936 where its official badge, depicting a racing greyhound surmounting the motto ‘Cave Canem’ (Beware of the Dog), was presented on 14 June 1937. At first the badge seems inappropriate for a bomber squadron but it is in fact indicative of the performance of the Hawker Hind when compared with its contemporaries. A move to Scampton in March 1938 was followed by conversion to the Handley Page Hampden, the first unit to be equipped with the type.

During the opening months of World War 2 the squadron was employed mainly on reconnaissance, mine laying and leaflet dropping. On 11 May 1940 bombing attacks on Germany began, the oil refineries at Munchen Gladbach being attacked. On 12 August a most successful low level attack on the Dortmund Ems canal was pressed home by Hampdens of 49 Squadron despite fierce opposition. Flt Lt R A B Learoyd received the Victoria Cross for his bravery during the attack, the first awarded in Bomber Command.

The squadron began to re equip with Manchester aircraft in April 1942; however, these aircraft were not in use for long and by July 1942 were replaced by Lancasters which, with their greater range and striking power, extended the scope of the squadron’s operations.

The Squadron stood down from 1-15 January 1943 during which time a move was made to Fiskerton. Operations resumed on 16 January when the squadron attacked Berlin the first of many such visits. For the remainder of the war the squadron continued as a front line bomber squadron and took part in most major operations by Bomber Command including, in August 1943, the vital attack on the rocket research establishment at Peenemunde when the squadron lost four of the twelve Lancasters despatched.

After moving to Fulbeck on 16 October 1944, then Syerston on 22 April 1945, the squadron made its last attack on 25 April when Berchtesgaden was the target. In May the squadron took part in Operation ‘EXODUS’ ferrying ex -prisoners of war back to the UK.

Honours and awards gained by members of 49 Squadron during the Second World War include 1 Victoria Cross, 1 Empire Gallantry Medal (later the George Cross), 7 Distinguished Service Orders, 131 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 2 Conspicuous Gallantry Medals and 105 Distinguished Flying Medals.

Following World War Two, the squadron flew Avro Lincolns and later the Vickers Valliant, the first of the V-bombers. It was in this aircraft that they would take part in the tests of Britain’s first nuclear weapons. From November 1959 the squadron reverted to the normal medium bomber role. It moved to Marham on 26 June 1961. On 5 June 1964 Her Royal Highness Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent, presented 49 Squadron with its standard, which was awarded in April.

49 Squadron was disbanded at RAF Marham on 1 May 1965, when all Valiant aircraft were withdrawn from service.

THE ACCIDENT

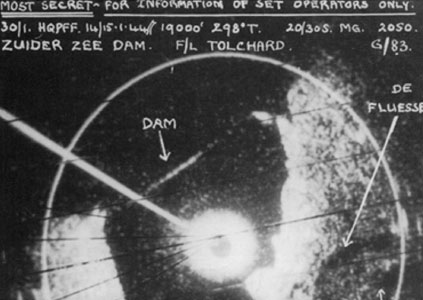

This was a special mission, for the very first time, we would be using the top-secret H2S radar. By this time in the war, technology was being developed that improved bombing accuracy. This was the targeting device that Bomber Command had needed so badly. The ground mapping H2S radar could give the Navigator an image of the target city at night and even through dense cloud. The radar was so advanced that there were serious concerns as to whether it should be used over enemy territory, lest it be captured and used by the Germans.

An image from an H2S radar.

We had successfully bombed our target in Hamburg and had returned to RAF Fiskerton with 10 other aircraft from our squadron. The weather at Fiskerton was not good, there was a 600ft cloud base with just 600 yards of visibility in rain. In fact, the weather was bad enough that the control tower suggested we divert to another airfield with better weather. 4 out of the squadrons 11 aircraft took that advice and diverted, but we, along with the rest, attempted to land at Fiskerton.

At 07:15hrs, our aircraft was seen to be way too low on the approach, suddenly rearing up before crashing. We hit a 40ft high tree, close to the Grimsby to Lincoln Railway line, just ¼ of a mile Northwest of the runway.

A Squadron investigation into the incident reported:

“The aircraft returned from its operational flight and contacted TR9 at Fiskerton for permission to land. Weather was poor with light rain and a cloud base of 600 feet. There was a searchlight canopy over the aerodrome and all available flares were laid out and lit. The aircraft made one low circuit of the aerodrome before its final approach. It was about 300 feet at this time, and was warned by TR9 of a slight crosswind when landing and low cloud. The aircraft came straight into the flare path on a very low approach and its port wing tip light was seen from the drome. The approach became lower and lower until finally the wing tip light was seen to rise sharply into the air and then disappear.

The aircraft was found a complete wreck about half a mile short of the runway having hit a 40 feet high tree on the approach. The survivor was questioned and it would appear that the pilot had set a wrong QFE on his altimeter. The Air Bomber was heard to say immediately before the crash “Get up, you are too low”, and then a few seconds later the aircraft hit a tree. There was no evidence of engine trouble and the aircraft had plenty of fuel.”

Reverend Hubert, whose wife Vi gives below a moving account of her time with the crew, buries them at Scampton.

Mrs Vi Hulbert, the wife of the Padre who was later to bury the crew, recalls the Christmas she had just shared with them:

“One Christmas I played the American organ in the large hangar on the aerodrome at Fiskerton It was Christmas morning; what a wonderful service we had and a grand turnout of airmen and WAAF. My husband conducted the service. It was a bitterly cold morning, with a strong wind blowing, but the singing of the Christmas hymns and carols by this large congregation was something to remember. We managed to have services on all the five bomber stations that morning and afterwards my husband and I were invited to lunch at one of the stations.

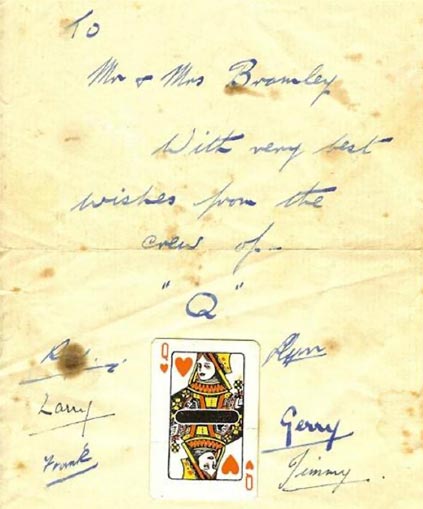

In the evening we returned to Scampton where they were having a dance. I noticed Llewellyn, who was an Australian aircrew officer looking so sad and not joining in. My husband and I asked if he and his friend Jerry would like to go with us to another station which we had to visit and then they could come back to our billet with us.

Llewellyn was very upset because he had not heard from his people in Australia for Christmas, the mails were late. Jerry, his Australian friend, had just been married and he did not get Christmas leave. I think enjoyed talking to us and we were able to help them that night although we got home very late.

I told them that if they would like to come to us for Christmas Dinner my husband and I would be delighted, as we were hoping to have Boxing Night for our Christmas. They were delighted to come. I managed to buy a chicken at the NAAFI store and a plum pudding. It was very difficult for me to get food as I only had my civilian ration book. They were so pleased as I had some tinned grapefruit, which I had brought, from our Rectory store cupboard when we left. It was Australian grapefruit, and this seemed to delight them. We had such a happy evening and it seemed to cheer them up.

Donald, my husband, drove them back to Scampton. The following week I remember so well, a cold snowy morning with a very strong wind blowing. Donald had gone to Scampton to welcome the aircrews back from operations. I was dressing and standing by my dressing table when I heard the roar of a plane, which seemed terribly low and somehow I sensed that it was in difficulty. I knew that Llewellyn and Jerry had gone on operations the night before and I felt so anxious somehow, as if I almost knew that it was going to be bad news.

Donald came back to our billet and I knew directly he came into our room by the expression on his face, that all was not well. I asked him if all the planes had landed safely on the aerodrome. He replied, “I’m afraid not.” I asked, “Was it Llewellyn and Jerry and their crew?” Donald replied, “Yes.” It did not seem possible somehow that they had returned safely from operations only to crash and all be killed. It was their plane that I had heard flying so low and circling round trying to land.

It was another of the many funerals that were held in the village church at Scampton, followed by a full RAF burial ceremony, which I had to attend. Donald conducted the service - Jerry’s wife and many relatives were there. After the service I went to speak to Jerry’s wife and the first thing she said was “Thank you for having Jerry out at Christmas. He wrote and told me all about it.” What a wonderful spirit of selflessness she showed, and how brave, not thinking of her own sorrow, remembering to say thank you to me.”

A card signed by the whole crew of Lancaster Q - Queenie.

CASUALTIES – 31ST JANUARY 1943

Flight Sergeant Elliot Livesey Cole (Pilot) RAAF (Buried Scampton) MORE

Flying Officer Frank Ridley (Navigator) RAF (Buried Scampton) MORE

Sergeant Frederick Stanley Tristram Pittard (Air Engineer) RAF (Buried Scampton) MORE

Flight Sergeant Llewellyn Grey (Wop/AG) RAAF (Buried Scampton) MORE

Sergeant James Arthur Gerald Browne (Wop/AG) RAAF (Buried Scampton)

ON THIS DAY IN WORLD WAR TWO – 31ST JANUARY 1943

Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus surrenders to a Russian Lieutenant in Stalingrad.

The German army in Stalingrad is defeated at the cost of 120,000 dead Germans.

RAF Bomber Command uses the revolutionary H2S radar for the first time on operations against Germany.

Where Next

Visit Lancaster PA474 at the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight RAF Coningsby.

BBMF Visitor Centre, Dogdyke Road, Coningsby, LN4 4SY Telephone: 01522 782040