SERVICE GRAVE

PETER WILSON STACEY (grave 43)

FLIGHT LIEUTENANT

MY STORY

Died: 30th May 1988

After the Vintage Pair disaster at Mildenhall, the Central Flying School had taken the decision to revive the historic flight with Meteor T7 WF791 taking the place of the lost aircraft. Almost exactly two years to the day since the previous accident, Flight Lieutenant Stacey was displaying the Meteor at Baginton near Coventry as part of the Warwickshire Air Pageant. Peter was three minutes into his display when he entered a wing-over, the aim of which was to return to the crowd line and show the aircraft with its undercarriage and flaps down.

At first, all seemed normal, but as the undercarriage was lowered the nose of the aircraft pitched down and it dived into the ground. Once again, the Meteor’s lack of ejector seats meant that the pilot was unable to escape and was killed on impact.

Those with experience of the Meteor when it was in frontline service with the Royal Air Force already knew what the Board of Enquiry would later discover. WF791 had fallen victim to the ‘Phantom Dive.’ At low speed, with air brakes out, the Meteor’s elevators would become ineffective and the aircraft would pitch down. All too often this occurred at low level and many Meteor pilots of previous generations had been killed by the aircraft’s worst vice.

Video evidence later showed that the whole display had been flown with the air brakes out. For the majority of the display this did not prove to be a problem, but as the aircraft slowed in the wing- over and the undercarriage was lowered, all the criteria for a classic Phantom Dive were in place. It is likely that Flight Lieutenant Stacey never realised the air brakes were out as they were still in this state when found in the wreckage.

What little control Peter had of the aircraft he used to steer it away from the Ernsford Grange housing estate on the edge of Coventry, crashing instead into a field. An eyewitness who saw the aircraft veer away from the houses was reported as saying: “If that is so, he was a very brave man indeed. If he had missed the trees he would certainly have hit the houses and the consequences would have been far worse.”

According to the local paper, reporting on the event, Peter had called the airport control tower and said “I’m coming down. I’m looking for open ground.”

Peter Stacey.

David Savery witnessed the tragic event as a child: He has written the following account on the Internet, but despite our best efforts we have been unable to trace him to discuss it. However we felt he would probably want his account to appear in this book. His appreciation of Peter Stacey’s actions is clear to see.

‘I lived in the suburb of Ernesford Grange in Coventry as a kid, about three miles from Coventry Airport (better known then as Baginton Airport). In May 1988 my dad and I were watching the annual Warwickshire Air Pageant from our back garden. It was hot and sunny and our proximity to the airfield meant we had a good free view of all manner of wonderful aircraft flying over our house as they took off from Baginton and turned around to be back on the return flight path.

Meteor on display at Newark Air Museum.

Me and my dad stood in the sunshine of the back garden and watched that Meteor streak across the blue sky from left to right with the sunshine bouncing off its frame. Then it turned towards us and lowered altitude. It didn’t register with me at the time and in fact, it wasn’t until I heard my dad telling the crash investigators later, that when it was just a couple of hundred metres above ground level and just a couple of hundred metres away, it was silent.

The roar of it’s engines had stopped and it was losing altitude and heading directly for our housing estate. Some people say the Meteor had fallen below stall speed by then, but I know what I saw.

Flt Lt Stacey knew if he hit the houses there would be massive loss of life and he took the split second decision to nose dive the stricken Meteor into a patch of open ground between the Willenhall and Ernesford Grange housing estates. I saw the Meteor in a controlled descent until that sudden nose dive.

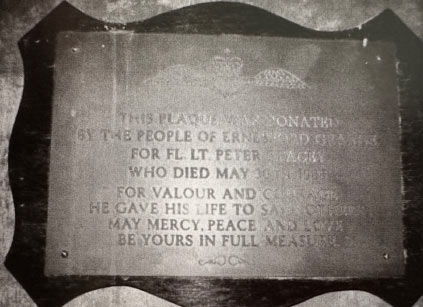

The brass plaque in Scampton church.

Sadly, the fuel laden plane exploded on impact into a massive fireball which bathed us in heat and left us knowing there was no hope of Flt. Lt. Stacey surviving. My father and I both ran out of the front of the house and around to the end of the road. The air was thick with smoke and the smell of aircraft fuel.

A police car which happened to have been travelling down Lang Bank Avenue was already parked up with two stunned looking Police officers radioing for help and telling the residents to keep back. A WM Travel bus had swerved to a stop on Langbank Avenue ahead of the Police car and according to the Coventry Evening Telegraph the driver had feared the plane was going to hit his double decker.

There’s no doubt in my mind that Flt Lt Stacey in his final seconds, saw that bus, the police car and the people in their gardens enjoying the bank holiday sunshine. Maybe he even saw me. Whatever he saw in those final moments, he bravely sacrificed his own life to avoid a major disaster. Over twenty years on, there are those of us who still remember.’

Certainly the local people were satisfied that Peter was a hero and had saved countless lives. His funeral was attended by representatives of Coventry Council, West Midlands Police and Baginton Airport Fire Brigade. Councillor Bill McKernan said “Flight Lieutenant Stacey died hopefully in the knowledge that he had saved the lives of many people. Undoubtedly he was an extremely brave man, because he kept his cool and took the plane away from homes”.

The crash site memorial.

A Memorial to his actions was placed at the site of the crash and in Scampton Church by the grateful residents.

Flight Lieutenant Stacey had served in the Royal Air Force for 10 years; he was a Qualified Flying Instructor at Scampton and was single. His funeral was attended by his elderly mother Ella Stacey who arrived on the arm of her remaining son Clive who lived in South Africa.

The RAF Scampton Chaplain, Reverend John Betteley led the service and in his address said “Peter was a man whose joy of flying was paramount to his life. I doubt whether he would have wanted to end his life in any other way than at the controls of an aircraft.”