SERVICE GRAVE

RAYMOND M. PARROTT (grave 69)

FLIGHT LIEUTENANT (Navigator)

MY STORY

Died: 20th September 1958

VX770 was the first Vulcan built and in 1952 made the types maiden flight in the hands of Avro Test Pilot, Wing Commander Roland “Roly” Falk.

But it was as a development aircraft that VX770 would secure a much less desirable place in the history books. In 1958, Rolls-Royce at Hucknall was developing a more powerful engine to power the Vulcan known as the Conway.

The Ministry of Supply, to assist the testing of the new engine, had lent them this aircraft. The testing was going well and the company had even managed to set a world record time flying to Rome.

On the day of the accident the civilian pilot, Keith Sturt, was on an engine test flight but he had also been given authority to perform a fly past at RAF Syerston’s Battle of Britain Day Air Display. His display was supposed to consist of two fly pasts at 200-300 feet at a speed of no greater than 300 knots. In the event he flew by at around 420 knots at a height of just over 60 feet.

On completion of the fly past, the pilot pulled up steeply and entered a turn. At this point, the stresses on the airframe became too great and panels on the starboard wing began to delaminate. Once the internal structure of the wing became exposed to the airflow it began to disintegrate. The aircraft crashed at the end of Syerston’s 07 runway, killing not only the entire crew, but also two airmen in the Runway Control Caravan and a third in a nearby rescue vehicle.

A further airman who was also in the rescue vehicle was badly injured.

Raymond Parrott was the only member of RAF personnel on board the aircraft; he had been on temporary secondment to Rolls-Royce from Scampton.

It is not known where the other members of the crew are buried, but some of those killed on the ground are buried in Newark Cemetery.

There was a great deal of controversy surrounding this crash and many suggested that the aircraft was not strong enough to handle such powerful engines. Investigations established that the aircraft had been over-stressed to such a degree that it stood no chance of survival. RAF Syerston had 20,000 visitors that day and the potential for a disaster of much greater proportions was evident to all.

Those who died alongside Flight Lieutenant Parrott were the pilot Mr Keith Sturt, the Second pilot Mr R W Ford and the Flight Engineer Mr W E Howkins. On the ground Sergeant E D Simpson, Sergeant C Hanson and SAC Tonks were killed. SAC Turnbull survived with injuries.

An extract from the Board of Enquiry Report follows:

‘Mr. K. Sturt, a Rolls-Royce test pilot, was authorised to fly the Conway Vulcan VX 770 from Hucknall on Saturday 20th September 1958. The flight was primarily for the Conway engine test programme, but at the conclusion of the flight, and if the timing was suitable, the aircraft was to carry out a fly past at Royal Air Force Syerston as part of Syerston’s Battle of Britain At Home programme; after the fly past the aircraft was to return to Hucknall, an adjacent airfield.

Mr. Sturt was briefed for this fly past by Mr. Heyworth, Rolls-Royce Chief Test Pilot. It was to be two runs over Syerston at 200 to 300 feet and between 250 and 300 knots at 70% to 80% engine revolutions, making the same manoeuvre that Mr. Sturt had done at Farnborough Air Display on 7th September 1958.

At 1235Z Vulcan VX 770 called Syerston tower giving an ETA at Syerston of 1255Z. At 1250Z the Vulcan called Syerston Tower saying it was approaching from the West, height 250 feet for a fast run followed by a slow run. Syerston Tower acknowledged this message and told the Vulcan that the airfield was clear until 1300Z.

At 1257Z the Vulcan approached Syerston from the West and commenced a run up the main 25/07 runway at an approximate height of 80 feet and an estimated speed of 350 knots.

A film taken at the time shows that when the aircraft was passing the Control Tower it started a roll to starboard and a slight climb; within 3/4 second a kink appeared in the starboard main plane leading edge approximately 9 feet outboard from the starboard engine intakes.

This was followed by a general stripping of the leading edge, the breaking off of the starboard wing tip and a general collapse of the main spar and wing structure between the spars. At this stage the wing was enveloped in a cloud of fuel vapour. The aircraft was now level, with the starboard wing broken off up to the undercarriage wheel well.

The Vulcan then went into a slight dive commencing a roll to port, which at 45 degree of bank, increased sharply at the same time shedding the tail fin. The remainder of the starboard wing was now on fire and the aircraft continued to roll to port with the nose lifting until the nose was vertical. The port wing leading edge began to crumble and fire broke out in the port wing.

The aircraft was now standing on its tail, travelling in plan form relative to the line of flight with the topside leading. The aircraft was then lost from view in an intense fire, reappearing with the nose pointing almost vertically downwards, having apparently continued its roll cum cartwheel. It continued in this attitude losing height until the topside of the nose struck the ground.

The port wing destroyed the fire/rescue Land Rover and runway controller’s caravan, killing all three of the occupants and injuring a fourth. All four members of the Vulcan crew were killed.

From the first indication of structural failure to the time of the crash was approximately 6 seconds. The wreckage trail extended over 1400 yards.’

The aircraft disintegrating.

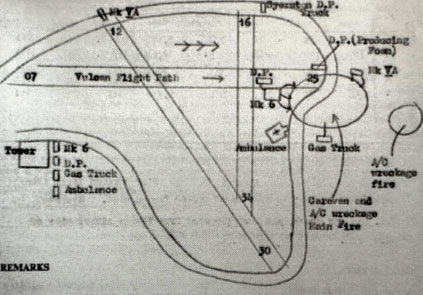

Original hand drawn plan of the crash site.